A Russian Translation of

Carl von Clausewitz, Vom Kriege (On War)

This Russian translation obviously dates from the Soviet era, given the Marxist-Leninist character of this introduction. It is the 1934 translation by A. K. Rachinsky, edited by A. A. Svechin [executed 1938] (Moscow: Gosvoyenizdat Publishing House, 1934). This edition of the translation [not the one pictured above, which is ISBN 9785699664863—modified versions of its cover illustration can be found on our Clausewitz Graphics page] was put out by publisher Eksmo, Midgard, in 2007. To get a rough sense of the conceptual content—which varies significantly in every translation—see this Google translation of the Russian version into English.

The complete 1934 Russian translation is provided HERE.

Provided further below is a Google translation into English of the original Introduction to this Russian translation. The Russian text is appended below the English translation. A better but technically somewhat complicated version of the 1934 Russian translation can be found at Militera.Lib.Ru.

This item appears to be the full text, or at least a substantial part of, Clausewitz's study "The Campaign of 1812 in Russia" on-line in Russian.

ОГЛАВЛЕНИЕ

ПОХОД В РОССИЮ 1812

г. Часть первая. Прибытие в Вильно. План кампании. Дрисский лагерь. Часть вторая. Дальнейший ход кампании.

ОБЩИЙ ОБЗОР СОБЫТИЙ ПОХОДА 1812 г. В РОССИЮ Первая часть. Первый период. Наступление французов до первой остановки в Вильно. Второй период. От конца первой остановки до второй остановки. Третий период. От попытки к наступлению русских главных сил до потери Москвы. Четвертый период. От занятия Москвы до начала отступления.

Вторая часть. От начала отступления до переправы главной армии через Неман. Обзор потерь, которые понес французский центр во время наступления и при отступлении.

* Первая публикация в сети Интернет в рамках проекта «1812 год». 20 октября 1998 г. Выполнено по изданию ГВИ Наркомата Обороны СССР 1937 г. В переводе А. К. Рачинского и М. П. Протасова под редакцией комдивов А. А. Свечина и С. М. Белицкого.

Библиотека интернет-проекта «1812 год». Публикацию электронной версии книги подготовил Поляков

SEE ALSO:

• The Russian Wikipedia page on Clausewitz. See this English translation (by Google, 24 June 2023, lightly edited).

• Lenin, V.I. "War and Revolution" [a lecture delivered 14 (27) MAY 1917). First published according to the shorthand report April 23, 1929 in Pravda No. 93. From Lenin Collected Works. Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1964, Moscow, Volume 24, pages 398-421. "We all know the dictum of Clausewitz, one of the most famous writers on the philosophy and history of war, which says: "War is a continuation of policy by other means." This dictum comes from a writer [See Clausewitz, On War, Vol. 1] who reviewed the history of wars and drew philosophic lessons from it shortly after the period of the Napoleonic wars. This writer['s...] basic views are now undoubtedly familiar to every thinking person...." Posted on-line by Marxists.org.

• Lenin, V.I. "Lenin's Notebook on Clausewitz." Ed./trans. Donald E. Davis and Walter S.G. Kohn. In David R. Jones, ed., Soviet Armed Forces Review Annual, vol.1. Gulf Breeze, FL: Academic International Press, 1977, pp.188-229. This text has been posted to ClausewitzStudies.org with the kind permission of Academic International Press. This is a translation of V.I. Lenin, "Notebook of Excerpts and Remarks on Carl von Clausewitz, On War and the Conduct of War, in V.V. Adoratskii, V.M. Molotov, and M.A Savel'ev, eds., Leninskii sbornik (Lenin Miscellany), (2nd ed., Moscow-Leningrad, 1931), XII, 389-452. Includes preface by A.S. Bubnov, explanatory notes by A. Toporkov, and considerable bibliographical information.

• Balakleets Natalia Alexandrovna [PhD in Philosophy, associate professor of the Department of Philosophy at Ulyanovsk State Technical University], Война, политика и субъект: философия военной деятельности Карла Клаузевица Текст научной статьи по специальности Философия, этика, религиоведение ["War, Politics, and the Subject: Karl Clausewitz's Philosophy of Warfare"}, 2017. This paper contains links to several other recent Russian papers that feature significant academic discussions about Clausewitz in Russian.

• Alexei Fenenko [PhD in History, RAS Institute of International Security Problems, RIAC expert] in "War of the Future—How Do We See It?," Russian International Affairs Council, 6 May 2016. "Back in the 1820s, the German military thinker Carl von Clausewitz distinguished two types of war—total war and limited war. They differ, according to Clausewitz, not in the number of dead and the scale of military actions, but in the model of victory. The aim of total war is to destroy the adversary as a political subject. The aim of limited war is to coerce the adversary into a desired compromise." It would be interesting to know if this is an accurate depiction of Fenenko's argument in the Russian original of his article and/or of the contents of the Russian translation of Vom Kriege that Fenenko cites (Moscow: Gosvoyenizdat Publishing House, 1934). In the German original, certainly, this description is erroneous.

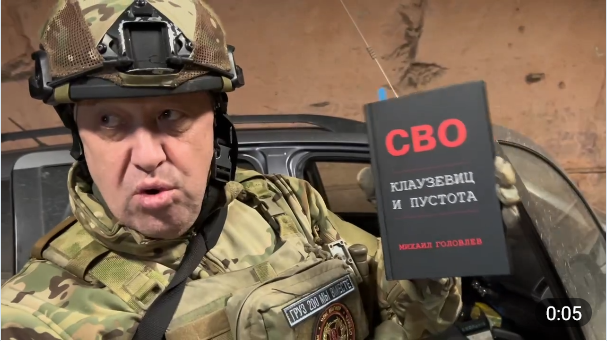

[Image made from original video, 15 April 2023 - 18:41]

Основатель ЧВК «Вагнер» Евгений Пригожин порекомендовал к прочтению книгу писателя Михаила Головлева. «СВО. Клаузевиц и пустота». Автор в своей работе описал основополагающую причину специальной военной операции на Украине.

[English: "The [late] founder of the Wagner PMC, Yevgeny Prigozhin, recommended reading a book by the writer Mikhail Golovlev. NWO. Clausewitz and Emptiness. The author in his work described the fundamental reason for the special military operation in Ukraine."]

Стратегия управления по Клаузевицу.

[Strategiya upravleniya po Klauzevitsu]

ISBN-10: 5945990426

ISBN-13: 978-5945990425

This is a Russian translation of Carl von Clausewitz, Clausewitz on Strategy, a book aimed at Fortune-500-level business CEOs. Edited by Tiha von Ghyczy, Bolko von Oetinger, and Christopher

Bassford.

Produced by the Boston Consulting

Group's Strategy Institute. Publisher: John Wiley

& Sons. ISBN: 0471415138. Amazon.com listing.

![A Russian officer presents a [very poor] rendition of the Wach portait to representatives of the Academy of the Bundeswehr on 18 May, 2004.](../images/RussianPortraitGift-2004.png)

Russian officers present a [particularly poor rendition of] a color portrait of the German military theorist Karl von Clausewitz to the leadership of the Academy of the Bundeswehr of the FRG at the Academy of Arts of Russia on May 18, 2004.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF THE 1934 RUSSIAN INTRODUCTION TO VOM KRIEGE

by Google Translator,

very lightly edited.

From the 2007 reprint:

Clausewitz's famous study "On War," which made up three volumes, outlines the author's views on the nature, goals and essence of war, the forms and methods of its conduct (and from which, in fact, the aphorism that received such wide popularity was extracted). It was the result of many years of studying military campaigns and campaigns from 1566 to 1815. Nevertheless, Clausewitz's work, purely specific in its original tasks, turned out to be in demand not only—and not so much—by military tacticians and strategists; descendants rightly ranked this work among the golden fund of strategic studies of a general nature, put it on a par with such examples of strategic thinking as Sun Tzu's treatises, The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli, and B. Liddell Hart.

From the original 1934 publisher:

The wide interest of our public in the theoretical works of Clausewitz explains the publication of the present, second edition of his main work "On War".

“It was a matter of ambition for me,” says Clausewitz about this work of his, “to write a book that would not be forgotten in 2-3 years, which those interested in the matter could pick up more than once.”

This hope of Clausewitz was fully realized: for more than a century, his book has been living, which created the author's well-deserved fame as a deep military theorist, philosopher of war.

Clausewitz was a contemporary of the great bourgeois revolution. The dictatorship of the Jacobins shattered the feudal feudal system in France. The new army created by the revolution victoriously defended its country from the onslaught of reactionary Europe and bravely cleared the way for a new social order with its weapons. "The French revolutionary troops drove out nobles, bishops and petty princes ... They cleared the ground, as if they were pioneers in virgin forests ..." (Engels). The old class privileges were crumbling everywhere. Everywhere the breath of the revolutionary storm was awakening the oppressed and ruined peasantry and the burghers, eking out a miserable existence.

The political ideas of the French Revolution remained alien and hostile to the Prussian nobleman Clausewitz. In this respect, he did not rise above the level of his class. Carl von Clausewitz is a monarchist. All his practical military activity was in the service of European reaction. As a fourteen-year-old boy, in 1793, Clausewitz took part in the Rhine Campaign, drinking away revolutionary France. In 1806 he participates in the war against Napoleon. In 1812, Clausewitz left the Prussian army and transferred to the service of Alexander I. He remained in the Russian service until 1814, participating in the Battle of Borodino, as well as in operations on the Lower Elbe and in the Netherlands. In 1815, having returned to the Prussian [ii] troops, Clausewitz was a quartermaster general of a corps in Blucher's army and participated in the battles of Ligny and Waterloo. After the July Revolution of 1830 in France, Clausewitz personally develops a plan for war against France. The political face of Clausewitz is also characterized by the fact that in 1810 the Prussian court elected him as a teacher for the heir to the throne - the crown prince. Clausewitz's monarchical convictions were also reflected in his main work, On War.

But being a determined enemy of the French Revolution, Clausewitz was able to understand the significance of the upheaval in military affairs caused by the revolution.

Together with all the participants in the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, Clausewitz experienced the brutal collapse of all the norms and provisions of the military art of the 17th and 18th centuries, which were considered "unchanging" and "eternal". The mass armies of the revolution took to the battlefields against the mercenary, carefully drilled armies of the reactionary coalitions. The new army of peasants, artisans and workers, inspired by the slogans of the revolution, found new ways of waging war, replacing the linear, strictly measured tactics, "oblique battle formations" of the mercenaries of Frederick II. The strategy of "cabinet" wars, similar to skillful swordsmanship, was replaced in revolutionary wars by a "plebeian" strategy of completely defeating the enemy. And on the fields of Jena and Auerstedt, together with the Prussian army, all the old familiar ideas about the art of war perished.

It was clear that within the framework of "pure" military art, within the framework of operational-strategic "monograms" and formations, one could neither explain the reasons for the defeat of the proud Prussian army, nor find ways to revive its military power. In the autumn of 1806, before the Battle of Jena, Scharnhorst, observing the maneuvering of French detachments, tried to imitate their military methods and discard Friedrich's tactics, but the very structure of the Prussian army, of course, made these attempts unsuccessful.

The principles of the French Revolution won a brilliant victory in military affairs as well. The recognition of their triumph was the struggle of the advanced military leaders of Prussia, among whom Clausewitz belonged, for military reform, for universal military service - on the basis of the elimination of serfdom. After Jena, Clausewitz took a practical part in this transformation of the army, working with Scharnhorst in the War Office.

The dilapidated building of the German Empire crumbled to dust under the blows of the revolution. Napoleon reshuffled countless German[iii] states. Under the onslaught of a foreign conqueror, the old Prussian state irrevocably collapsed in the catastrophe at Jena.

Backward, semi-feudal Germany, in the person of its young bourgeoisie, was awakening to a new life. But the German bourgeoisie was too weak to embark on the path that had been victoriously traveled before by its French and English brethren. Germany in this period was still only on the eve of the industrial revolution, which began in it only in the 40s of the XIX century. In the era of Clausewitz, German capitalism developed on the basis of domestic industry. Machinery was in its infancy. The backwardness of German capitalism, which had grown up under the auspices of the landlord government, determined the weakness of the German bourgeoisie. It was incapable of a decisive struggle for a new social order. But the brutal military defeat of Prussia in 1806 clearly showed the need for bourgeois reforms. Subject to the relentless pressure of circumstances, even the Prussian landowners realized that only the peasantry liberated from serfdom was capable of reviving the military might of Germany. It was clear that without some, even if only visible, concessions, it was impossible to rouse the Prussian peasant to fight against Napoleon. In addition, the Junkers feared that the emancipation of the peasantry might, as a result of new defeats, come from outside, from the victorious French, or from below, from the peasant revolution. The bitter experience learned from a series of shameful defeats led to the bourgeois reforms of Stein-Hardenberg (the beginning of the emancipation of the peasants and a new urban structure) and the military reforms of Scharnhorst (the transition to short terms of service in the army and universal military service). it is impossible to rouse the Prussian muzhik to fight Napoleon with even visible concessions. In addition, the Junkers feared that the emancipation of the peasantry might, as a result of new defeats, come from outside, from the victorious French, or from below, from the peasant revolution. The bitter experience learned from a series of shameful defeats led to the bourgeois reforms of Stein-Hardenberg (the beginning of the emancipation of the peasants and a new urban structure) and the military reforms of Scharnhorst (the transition to short terms of service in the army and universal military service). it is impossible to rouse the Prussian muzhik to fight Napoleon with even visible concessions. In addition, the Junkers feared that the emancipation of the peasantry might, as a result of new defeats, come from outside, from the victorious French, or from below, from the peasant revolution. The bitter experience learned from a series of shameful defeats led to the bourgeois reforms of Stein-Hardenberg (the beginning of the emancipation of the peasants and a new urban structure) and the military reforms of Scharnhorst (the transition to short terms of service in the army and universal military service).

The public upsurge after the catastrophe at Jena engulfed the whole of Germany. From the Berlin pulpit, Fichte addressed fiery speeches to the German nation. Heinrich Kleist in his poems called for a fight against foreign invaders. But the ardent patriotism of the German bourgeoisie, which raised the banner of German unification, ultimately went to the service of reaction. The struggle of the bourgeoisie for national liberation, for national unity was exploited by the Junkers and contributed to the restoration of the old order. The twenty-year era of revolutionary wars ended with the victory of reactionary Europe. The German bourgeoisie could derive nothing from the fruits of this victory. Economic weakness did not allow her to embark on a revolutionary path and pushed her towards reconciliation with the ruling feudal estates. [iv]

The impotence and opportunism of the German bourgeoisie found their vivid expression in German classical philosophy. The bourgeoisie, which practically did not set itself the task of fighting the existing system, lived in a world of abstract thought. German idealist philosophy was a pale reflection of the French Revolution, carried over into the realm of ideas. Under the undoubted influence of classical German idealism, Clausewitz's doctrine of war was created.

Brought up on Kant, Montesquieu and Machiavelli, having listened to the philosophical lectures of the Kantian Kiesewetter after Jena, Karl Clausewitz worked on his main work "On War" in the years (1818 - 1830), when Hegel reigned supreme over the minds of Germany. The direct philosophical origins of Clausewitz's teachings lead to Hegel: from Hegel - Clausewitz's idealism, from Hegel his dialectical method.

Clausewitz's doctrine of war reflected the main features of the ideology of the early period of capitalism.

Clausewitz is first and foremost a philosopher. “Now I am reading Clausewitz’s On War, by the way,” writes Engels in 1858, “a peculiar way of philosophizing, but in essence very good.”

In connection with his studies in philosophy, V. I. Lenin studied Clausewitz during the years of the imperialist war.

Clausewitz worked on his main work "On War" during the last 12 years of his life, being the director of a military school (academy) in Berlin. This work of Clausewitz was published only after his death. Clausewitz's work remained unfinished. Different parts of the work are developed unevenly. In some places, the lack of a final edition is reflected. But this unfinished work, which was characterized by the author as "a formless heap of thoughts", stands incomparably higher than anything that the theoretical thought of the old world gave in the field of analysis of war and military art. Clausewitz is the pinnacle of bourgeois military theory.

In his study of military questions, he resolutely renounced the methods of formal logic and metaphysics that have dominated and continue to dominate bourgeois military science. In the dialectical method, in the concreteness and comprehensiveness of analysis, which is alien to any schematic, lies the immortal significance of Clausewitz's work.

The merit of Clausewitz lies in the fact that he was the first to correctly pose the basic problems of military theory. Clausewitz does not create an "eternal" strategic theory, does not provide a textbook with ready-made [v] dogmatic formulas. He considers the task of strategy to be the study of the phenomena of war and the art of war. He is trying to reveal the dialectic of war and to reveal the basic principles and objective regularity of its processes.

Clausewitz worked hard on history. Most of his writings are devoted to a critical analysis of the wars of the XVIII century. This preliminary research work and his personal experience led Clausewitz to deny the "eternal principles" of military art. He regards such "immutable rules" as a direct source of cruel defeats, as an indicator of the poverty and inertia of military thought. “Every epoch,” says Clausewitz, “had its own wars, its own limiting conditions and its own difficulties. Each war would therefore also have its own theory, even if everywhere and always people were disposed to work out theories of war on the basis of philosophical principles. ".

Clausewitz carefully and comprehensively examines the changes in the nature of war in different eras, considering the phenomena of war and military art in their development and movement.

Clausewitz is a dialectician. He studies the dynamics of each military phenomenon, revealing the pattern of its development and the internal mechanics of its transformations. Through all the studies of Clausewitz, the main idea runs like a red thread that war moves and develops in contradictions. Clausewitz considers all phenomena of military reality from the point of view of the basic dialectical law of unity and mutual penetration of opposites. He does not oppose defense to offensive, crushing to starvation, as the epigones of bourgeois military thought still do. On the contrary, in the offensive he does not cease to see the defense, and in the defense the offensive. "Every means of defense leads to a means of attack. But they are often so close that you can notice them without going over from the point of view of defense to the point of view of attack: one by itself leads to another." " Defense does not consist in unconditional waiting and fighting off. She... is more or less imbued with the beginning of the offensive. In the same way, the offensive is not entirely homogeneous, but is always mixed with defense. "The offensive in war will, especially in strategy, be a constant change from offensive to defensive."

A representative of the early period of capitalism, Clausewitz was ten heads taller than the last of bourgeois military thought, unable to get out of the quagmire of metaphysics. [vi] War seems to Clausewitz "a real chameleon, since it changes its nature in each specific case. Describing war as "a manifestation of violence, the use of which there can be no limits", he clearly sees such wars that are waged only to help negotiations and consist only in the threat to the enemy.

Clausewitz also approaches dialectically the paths leading to victory. Along with the two main types - a war that seeks to crush the enemy, and a war that solves problems of a local and private nature - he sees a number of intermediate forms. It is clear to him that it is impossible to dogmatize any specific methods of waging war, the choice of which should be determined exclusively by the specific situation. “Depending on the circumstances,” he says, “it is possible to use with success various suitable means, which are: the destruction of the enemy’s fighting forces, the conquest of his provinces, their simple occupation, any enterprise that affects political relations, and, finally, passively waiting for the enemy’s blows. The choice of each of the means depends on the circumstances of each given case.

Clausewitz clearly distinguishes between the character of war in the political sense and its strategic character. “A politically defensive war is a war that is waged to defend one’s independence; a strategically defensive war is a campaign in which I limit myself to fighting the enemy in that theater of military operations that I have prepared for myself for this purpose. Do I give battles in this theater of war offensive or defensive in nature, this does not change matters. Thus, a politically defensive war can be offensive in the strategic sense, and vice versa: "it is possible to defend one's own country on enemy soil," says Clausewitz.

The dialectic of Clausewitz is vividly developed in his refusal to recognize the self-sufficient significance of the war. Despite his idealism, he sees that war "is a special manifestation of social relations." Clausewitz therefore does not close himself within the framework of the study of the external forms of strategy. Central to the teachings of Clausewitz is the idea of war growing out of politics: "War is nothing but the continuation of state policy by other means."

To the chapter in which Clausewitz examines in particular detail the question of the dependence of war on politics (Part III, Ch. 6), Lenin made a note in his extracts: "The most important chapter." [viii]

The greatest merit of Clausewitz lies in the fact that he resolutely rejected the notion of war as an independent phenomenon, independent of social development.

"... Under no circumstances," writes Clausewitz, "we should not think of war as something independent, but as an instrument of politics. Only with this representation is it possible to avoid contradiction with the entire military history. Only with this representation this great book becomes accessible secondly, it is precisely this understanding that shows us how different wars must be in terms of the nature of their motives and the circumstances from which they arise.

Without politics, war is impossible. Wars in human society have always been caused by political motives. "War in human society - the war of entire peoples and, moreover, civilized peoples - always follows from the political state and is caused only by political motives," writes Clausewitz.

Clausewitz considers a number of wars in history from this point of view and proves that their character was entirely determined by the politics of which they were an instrument.

In the light of Marxism-Leninism, this analysis of the nature of the wars of past history is very limited and helpless, as it proceeds from Clausewitz's idealistic ideas about society and politics. But how much he nevertheless outstripped his contemporaries, is shown by the fact that until now bourgeois military theoreticians not only have not gone further in developing the positions expressed by the great military thinker, but have remained alien to them.

The greatest theoreticians of the bourgeoisie still continue to regard war as a phenomenon inherent in human nature, eternal and inevitable as long as peace exists. This is the position taken by all the numerous bourgeois theories about the origin of wars: biological, racial, psychological, etc. Their purpose is clearly to prove to the oppressed classes the senselessness of fighting wars waged in the interests of capital.

Clausewitz, defining war as a continuation of politics by other means, at the same time points out that war is a special, specific phenomenon. “War is,” he wrote, “a definite matter (and such a war will always remain, no matter how broad interests it would affect, and even in the case when all the men of a given people who are able to bear arms are called to war), it is an excellent and isolated matter.” [viii]

Referring elsewhere to this question, Clausewitz says that what is specific in war refers to the nature of the means employed by it. Everything that has to do with the armed forces, their organization, preservation, strengthening, and use belongs to the sphere of specifically military activity. However, noting the specifics of war, Clausewitz everywhere emphasizes that war is part of the whole, and this whole is politics.

For Clausewitz, war is only an instrument of politics, a special form of political relations. Politics determines the nature of war. Changes in the art of war are the result of a change in policy. In the eyes of Clausewitz, the art of war is politics, "changing the pen for the sword." Therefore, Clausewitz resolutely fights all attempts to subordinate the political point of view to the military one. He speaks of these attempts as nonsense, "because politics gave rise to war. Politics is reason, war is only a tool, and not vice versa."

In the light of Marxism-Leninism, Clausewitz's interpretation of war as a social phenomenon has only the significance of the greatest achievement of bourgeois military science. The fundamental defect of his theory lies in the idealistic understanding of politics. Politics for him is an expression of the interests of the whole society, the concentrated mind of the state. Understanding the dependence of war on politics, on social conditions, Clausewitz was unable to go beyond this.

The limited bourgeois outlook deprived Clausewitz of the opportunity to understand the driving forces behind the development of politics itself, as a historical form of social development, the content of which is the class struggle. Clausewitz did not see that wars are generated on the basis of a clash of economic interests, on the basis of the class struggle, because he did not understand that politics is a concentrated economy, a class struggle. And so the true nature of the wars remained a mystery to him. He naively considered wars "people's" if the masses of the people participated in them, being forcibly drawn into the armed struggle. He did not understand that the wars of Prussia and other small German states against Napoleon were popular not at all because the masses of the people actively participated in them, in connection with the formation of the army on the basis of universal military service: they assumed a national liberation, "people's" character only when the struggle began against the dictatorship of Napoleon, for the national liberation and unification of Germany. But even under these conditions, the allies of Prussia in 1813-1815. - England and Russia of Alexander I - waged a reactionary war. [ix]

In the world war of 1914-1918. huge masses of workers and laborers took part. Almost the entire population of the belligerent countries was involved in the war in one form or another, and despite this, the war was, of course, not a people's war, but, on the contrary, predatory, "against the people", imperialist. The war of the imperialist predators against the USSR will also be counter-revolutionary in character, while the war on the part of the proletarian state will be a revolutionary, just, people's war.

The idealist Clausewitz does not see classes and class struggle: before him is always a formless "people".

The change in social relations and the "spirit" of the people is for him an inexplicable mystery. Ultimately, the "spirit" becomes the last mainspring of the movement and development of social relations and wars themselves.

The idealistic understanding of politics did not allow this truly deep thinker to understand the true nature of wars both in history and in his contemporary era.

Establishing the method of his research, Clausewitz elevates war to an absolute level. This abstract concept of absolute war is contrasted with its imperfect reflection - genuine historical wars. The influence of German idealistic philosophy, which is clearly manifested here, leads to the main contradiction in the teachings of Clausewitz, for the theory of self-disclosure of the concept of absolute war is clearly incompatible with his basic proposition about war as a continuation of politics.

The strategic views of Clausewitz sum up the revolution in military affairs that the French Revolution brought about. If, according to Clausewitz, tactics is "the doctrine of the use of armed forces in combat", then strategy is "the doctrine of the use of battles for the purposes of war." Clausewitz considers the organization of a general battle to be the central decisive task of the generalship, by which he means not an ordinary battle, of which there are many in a war, but "... a battle of the main mass of the armed forces ... with full exertion of forces for a complete victory." Clausewitz believed that only great decisive victories lead to great decisive results. Hence his conclusion: "a great decision - only in a great battle."

But Clausewitz knows that solving strategic problems outside the concrete conditions and tasks of a given war is nonsense. This is the scholasticism that K. Clausewitz hated and fought against - "is it possible," he asks, "to design a campaign plan without taking into account the political state and capabilities of the state." [x]

The nature of politics also determines the nature of war - this is the main position of Clausewitz. "The nature of the political goal has, in fact, a decisive influence on the conduct of war" - "when politics becomes grander and more powerful," writes the military thinker, "so does war."

But while correctly establishing that the political elements of war determine the strategic line of conduct, Clausewitz did not understand, however, that the nature of the strategy is also determined by the nature of the armed organization, its social nature, numbers, as well as the quantity and quality of equipment that it has at its disposal.

In his writings, there is no analysis of the influence of the nature of the army on the conduct of the war. Of course, he saw the difference between the soldiers of the revolution and mercenaries, but the true essence of the army, its nature, the foundations of its discipline and combat effectiveness remained a mystery to him.

Clausewitz gave a great place in his works to the importance of moral elements in the conduct of war, but reduced everything to arguments about military genius, about the valor of the army, about cunning, firmness, courage, i.e. to moments that are important in the cause of war, but which, apart from concrete reality, are empty abstractions. Along with the deep thoughts of the great theoretician, such passages in his work sound naive: "Military prowess is inherent only in standing armies"; or: "The genius of the commander is able to replace the spirit of the army when it is possible to keep it assembled."

Clausewitz also did not understand the full significance of military technology, which directly determines the method of waging war. In the few glories that Clausewitz dropped about military equipment, his idealism is fully visible. It is not the nature of the weapons that influences the conduct of the war, but vice versa: "Combat determines the weapons and organization of the troops."

The idealism of Clausewitz is, of course, incompatible with science. The military-organizational and military-technical aspects of his theory are clearly outdated. And yet the works of Clausewitz represent the most valuable of all that bourgeois military thought has given. It is from this point of view that we consider Clausewitz and study his theory.

Marxism-Leninism, paying tribute to Clausewitz, "whose basic ideas have now become the unconditional acquisition of every thinking person" (Lenin), gave a fundamentally different from the teachings of Clausewitz, free from idealistic distortions, the only scientific understanding of war, as "the continuation of the policy of different classes in given time." [xi] Lenin during the years of the imperialist war carefully studied the work of Clausewitz. Lenin concentrated his main attention on Clausewitz's doctrine of the relation of war to politics and on his application of dialectics to various aspects of military affairs. More than once Lenin directed the dialectical propositions of his teaching against the sophistry of the social-chauvinists, against Kautsky and Plekhanov. In the pamphlet "Socialism and War" one of the sections is titled directly with a quote from Clausewitz: " War is the continuation of politics by other (namely, violent) means. "This famous saying," Lenin writes further, "belongs to one of the most profound writers on military questions, Clausewitz. Marxists rightly considered this proposition to be the theoretical basis of their views on the significance of each given war. Marx and Engels always looked at various wars from this point of view" (Lenin, Sobr. soch., vol. XIII, p. 97).

In the article "The Collapse of the Second International" Lenin again points out that "as applied to wars, the basic tenet of the dialectic, so shamelessly perverted by Plekhanov to please the bourgeoisie, is that "war is simply the continuation of politics by other (namely, violent) means." Such is the formulation Clausewitz, one of the great writers on military history, whose ideas were fertilized by Hegel. And that was always the point of view of Marx and Engels, who considered every war as a continuation of the policy of these interested powers and different classes within them at a given time "(Lenin, Sobr op. vol. XIII, pp. 144 - 145). In the same footnote, Lenin quotes from Clausewitz as follows: “Everyone knows that wars are caused only by political relations between governments and between peoples; but they usually conceive of the matter as if from the beginning of the war these relations cease and a completely different situation sets in, subject only to its own special laws. We affirm the opposite: war is nothing but the continuation of political relations with the intervention of other means. "V.I. Lenin uses this provision to expose Kautsky's sophistry: "If we look closely at the theoretical premises of Kautsky's reasoning, we will get exactly the view that is ridiculed Clausewitz about 80 years ago" (Lenin, Sobr. soch., Vol. XIII, p. 145).

Lenin later referred to Clausewitz in his struggle against the "left" communists. "We demand from everyone a serious attitude to the defense of the country," Lenin wrote in his article "On the" left "childishness [xii] and petty-bourgeoisness. "To be serious about the defense of the country means to prepare thoroughly and strictly take into account the balance of forces. If there are obviously few forces, then the most important means of defense is a retreat into the interior of the country (whoever would see in this, for the present case only a drawn formula, can read from old Clausewitz, one of the great military writers, about the results of the lessons of history on this subject). there is not even a hint that they understand the significance of the question of the correlation of forces" (Lenin, Sobr. soch., vol. XV, pp. 240 - 241).

The extracts and remarks by Lenin on Clausewitz's book On War published in the 12th Lenin Miscellany are of great guiding methodological significance: they indicate how one should read and study the works of the great bourgeois theoretician.

We need the idealistic teaching of Clausewitz, of course, not for the development of our theory of war.

The Marxist-Leninist doctrine of war is based on materialist dialectics. Our proletarian theory of war is exhaustively given in the works of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, in the decisions of our Party and its Central Committee. But the experience made by Clausewitz in applying idealistic dialectics to practical military activity must be carefully and comprehensively taken into account by us. This critical account can, to a certain extent, help us to use the powerful weapon of Marx-Lenin's materialist dialectics in the field of analysis of concrete military reality.

The present, second, edition of Clausewitz's work "On War" is published after the necessary verification and correction of the translation.

The publishing house did not consider it necessary to accompany the translation with a critical commentary and a detailed preface, considering the indications given in the book to all the extracts and remarks made by V. I. Lenin to be completely sufficient. [xiii]

Карл фон Клаузевиц О ВОЙНЕ

Издательства: Эксмо, Мидгард

2007 г.

Составившее три тома знаменитое исследование Клаузевица "О войне", в котором изложены взгляды автора на природу, цели и сущность войны, формы и способы ее ведения (и из которого,

собственно, извлечен получивший столь широкую известность афоризм), явилось итогом многолетнего изучения военных походов и кампаний с 1566 по 1815 год. Тем не менее сочинение

Клаузевица, сугубо конкретное по своим первоначальным задачам, оказалось востребованным не только - и не столько - военными тактиками и стратегами; потомки справедливо причислили эту

работу к золотому фонду стратегических исследований общего характера, поставили в один ряд с такими образцами стратегического мышления, как трактаты Сунь-цзы, "Государь" Никколо

Макиавелли и "Стратегия непрямых действий" Б.Лиддел Гарта.

От издательства

Широкий интерес нашей общественности к теоретическим трудам Клаузевица объясняет выпуск в свет настоящего, второго издания его основной работы "О войне".

- "Для меня было вопросом честолюбия, - говорит Клаузевиц об этом своем труде - написать такую книгу, которую бы не забыли через 2-3 года, которую интересующиеся делом могли бы взять в руки не один лишний раз".

Эта надежда Клаузевица осуществилась полностью: уже больше столетия живет его книга, создавшая автору заслуженную славу глубокого военного теоретика, философа войны.

Клаузевиц был современником великой буржуазной революции. Диктатура якобинцев вдребезги разбила феодальный крепостнический строй во Франции. Созданная революцией новая армия победоносно отстаивала свою страну от натиска реакционной Европы и отважно расчищала своим оружием дорогу для нового социального строя. "Французские революционные войска прогоняли дворян, епископов и мелких князей... Они расчищали почву, точно они были пионерами в девственных лесах..." (Энгельс). Повсюду рушились старые сословные привилегии. Повсюду дыхание революционной бури пробуждало угнетенное и разоренное крестьянство и влачившее жалкое существование бюргерство.

Политические идеи французской революции ост ались чужды и враждебны прусскому дворянину Клаузевицу. В этом отношении он не возвышался над уровнем своего класса. Карл фон Клаузевиц - монархист. Вся его практическая военная деятельность прошла на службе европейской реакции. Четырнадцатилетним мальчиком, в 1793 г., Клаузевиц принимает участие в Рейнской кампании пропив революционной Франции. В 1806 г. он участвует в войне против Наполеона. В 1812 г. Клаузевиц покидает прусскую армию и переходит на службу к Александру I. На русской службе он остается до 1814 г., участвуя в Бородинском сражении, а также в операциях на Нижней Эльбе и в Нидерландах. В 1815 г., вернувшись в прусские [ii] войска, Клаузевиц состоит генерал квартирмейстером корпуса в армии Блюхера и участвует в сражениях при Линьи и Ватерлоо. После июльской революции 1830 г. во Франции Клаузевиц лично разрабатывает план войны против Франции. Политическое лицо Клаузевица характеризуется также тем, что в 1810 г. прусский двор избрал его в качестве преподавателя для наследника престола - кронпринца. Монархические убеждения Клаузевица нашли свое отражение и в его основном труде "О войне".

Но будучи решительным врагом французской революции, Клаузевиц сумел понять значение переворота в военном деле, вызванного революцией.

Вместе со всеми участниками революционных и наполеоновских войн Клаузевиц пережил жестокое крушение всех, считавшихся "неизменными" и "вечными", норм и положений военного искусства ХVII и XVIII столетия. На поля сражений против наемных, тщательно вымуштрованных армий реакционных коалиций выступили массовые армии революции. Новая армия крестьян, ремесленников и рабочих, воодушевленная лозунгами революции, нашла новые способы ведения войны, заменившие линейную, строго размеренную тактику, "косые боевые порядки" наемников Фридриха II. Стратегия "кабинетных" войн, похожая на искусное фехтование, сменилась в революционных войнах "плебейской" стратегией полного разгрома противника. А на полях Йены и Ауэрштедта вместе с прусской армией погибли все старые привычные представления о военном искусстве.

Было ясно, что в рамках "чистого" военного искусства, в пределах оперативно-стратегических "вензелей" и построений нельзя ни объяснить причин поражения гордой прусской армии, ни найти пути для возрождения ее военной мощи. Осенью 1806 г., перед Йенской битвой, Шарнгорст, наблюдая маневрирование французских отрядов, пытался подражать их военным приемам и отбросить фридриховскую тактику, но самое устройство прусской армии, конечно, сделало эти попытки безуспешными.

Принципы французской революции одержали блестящую победу и в военном деле. Признанием их торжества была борьба передовых военных деятелей Пруссии, к числу которых принадлежал и Клаузевиц, за военную реформу, за всеобщую воинскую повинность - на базе ликвидации крепостного права. После Йены Клаузевиц принимал практическое участие в этом преобразовании армии, работая вместе с Шарнгорстом в военном министерстве.

Ветхое здание германской империи под ударами революции рассыпалось в прах. Наполеон перетасовывал бесчисленные немецкие [iii] государства. Под натиском иноземного завоевателя бесповоротно рухнуло в катастрофе при Йене старое прусское государство.

Отсталая, полуфеодальная Германия, в лице ее молодой буржуазии, пробуждалась к новой жизни. Но германская буржуазия была слишком слаба для того, чтобы вступить на путь, победоносно пройденный перед тем ее французскими и английскими собратьями. Германия в этот период стояла еще только накануне промышленного переворота, начавшегося в ней лишь в 40-х годах XIX в. В эпоху Клаузевица германский капитализм развивался на базе домашней промышленности. Машинная техника находилась в зачаточном состоянии. Отсталость германского капитализма, выросшего под покровительством помещичьего правительства, определяла слабость германской буржуазии. Она была неспособна к решительной борьбе за новый общественный строй. Но жестокий военный разгром Пруссии в 1806 г. со всей очевидностью показал необходимость буржуазных реформ. Подчиняясь неумолимому давлению обстоятельств, даже прусские помещики поняли, что только освобожденное от крепостных пут крестьянство способно возродить военную мощь Германии. Было ясно, что без некоторых, хотя бы только видимых, поблажек невозможно поднять прусского мужика на борьбу с Наполеоном. Кроме того, юнкерство опасалось, что освобождение крестьянства может в результате новых поражений прийти извне, от победителей-французов, или снизу, от крестьянской революции. Горький опыт, вынесенный из ряда позорных поражений, привел к буржуазным реформам Штейна - Гарденберга (начало освобождения крестьян и новое городское устройство) и военным реформам Шарнгорста (переход к коротким срокам службы в армии и всеобщей воинской повинности).

Общественный подъем после катастрофы при Йене охватил всю Германию. С берлинской кафедры Фихте обращался с пламенными речами к германской нации. Генрих Клейст в своих поэмах призывал к борьбе с иноземными завоевателями. Но горячий патриотизм немецкой буржуазии, поднявшей знамя объединения Германии, пошел в конечном счете на службу реакции. Борьба буржуазии за национальное освобождение, за национальное единство эксплуатировалась юнкерством и содействовала восстановлению старого порядка. Двадцатилетняя эра революционных войн завершилась победой реакционной Европы. Из плодов этой победы немецкая буржуазия не могла извлечь ничего. Экономическая слабость не позволила ей встать на революционный путь и толкала ее на примирение с господствующими феодальными сословиями. [iv]

Бессилие и оппортунизм немецкой буржуазии нашли свое яркое выражение в германской классической философии. Буржуазия, практически не ставившая перед собой задачи борьбы с существующим строем, жила в мире отвлеченной мысли. Немецкая идеалистическая философия явилась бледным отражением французской революции, перенесенной в царство идей. Под несомненным влиянием классического немецкого идеализма создавалось учение Клаузевица о войне.

Воспитанный на Канте, Монтескье и Макиавелли, прослушавший после Йены философские лекции кантианца Кизеветтера, Карл Клаузевиц работал над своим основным трудом "О войне" в годы (1818 - 1830), когда над умами Германии безраздельно властвовал Гегель. Непосредственные философские истоки учения Клаузевица приводят к Гегелю: от Гегеля - идеализм Клаузевица, от Гегеля его диалектический метод.

В учении Клаузевица о войне отразились основные черты идеологии раннего периода капитализма.

Клаузевиц - прежде всего философ. - "Я читаю теперь между прочим Клаузевица "О войне", - пишет Энгельс в 1858 г., - своеобразный способ философствовать, но в сущности очень хорошо".

В связи с занятиями по философии изучал Клаузевица в годы империалистической войны В. И. Ленин.

Над своим основным трудом "О войне" Клаузевиц работал в течение последних 12 лет своей жизни, будучи директором военной школы (академии) в Берлине. Этот труд Клаузевица был опубликован лишь после его смерти. Работа Клаузевица осталась незаконченной. Различные части труда разработаны неравномерно. Сказывается местами отсутствие окончательной редакции. Но этот незаконченный труд, который характеризовался автором, как "бесформенная груда мыслей", стоит несравненно выше всего, что дала теоретическая мысль старого мира в области анализа войны и военного искусства. Клаузевиц - вершина буржуазной военной теории.

Он решительно отказался в своем исследовании военных вопросов от методов формальной логики и метафизики, которые господствовали и господствуют в буржуазной военной науке. В диалектическом методе, в конкретности и всесторонности анализа, чуждого всякой схематичности, заключается бессмертное значение труда Клаузевица.

Заслуга Клаузевица состоит в том, что он впервые правильно поставил основные проблемы военной теории. Клаузевиц не создает "вечной" стратегической теории, не дает учебника с готовыми [v] догматическими формулами. Задачей стратегии он считает исследование явлений войны и военного искусства. Он пытается вскрыть диалектику войны и выявить основные принципы и объективную закономерность ее процессов.

Клаузевиц много работал над историей. Большая часть его сочинений посвящена критическому разбору войн XVIII столетия. Эта предварительная исследовательская работа и его личный опыт привели Клаузевица к отрицанию "вечных принципов" военного искусства. Он расценивает такие "неизменные правила" как непосредственный источник жестоких поражений, как показатель убожества и косности военной мысли. "Всякая эпоха, - говорит Клаузевиц, имела свои собственные войны, свои собственные ограничивающие условия и свои затруднения. Каждая война имела бы, следовательно, также свою собственную теорию, если бы даже повсюду и всегда люди были бы расположены обрабатывать теории войны на основе философских принципов".

Клаузевиц тщательно и всесторонне исследует изменения характера войны в различные эпохи, рассматривая явления войны и военного искусства в их развитии и движении.

Клаузевиц - диалектик. Он изучает динамику каждого военного явления, вскрывая закономерность его развития и внутреннюю механику его превращений. Через все исследования Клаузевица красной нитью проходит основная мысль, что война движется и развивается в противоречиях. Все явления военной действительности Клаузевиц рассматривает под углом зрения основного диалектического закона единства и взаимного проникновения противоположностей. Он не противопоставляет оборону наступлению, сокрушение - измору, как это делают до сих пор эпигоны буржуазной военной мысли. Наоборот, в наступлении он не перестает видеть оборону, а в обороне наступление. "Всякое средство обороны ведет к средству наступления. Но они часто так близки, что заметить их можно и не переходя с точки зрения обороны на точку зрения атаки: одно само собой ведет к другому". "Оборона не состоит в безусловном ожидании и отбивании. Она... более или менее проникнута началом наступления. Точно так же и наступление не сплошь однородно, но всегда смешано с обороной". "Наступление на войне будет, в особенности в стратегии, постоянной сменой наступления обороной".

Представитель раннего периода капитализма, Клаузевиц был десятью головами выше последышей буржуазной военной мысли, никак не могущих выбраться из трясины метафизики. [vi] Война представляется Клаузевицу "настоящим хамелеоном, так как она в каждом конкретном случае изменяет свою природу. Характеризуя войну как "проявление насилия, применению которого не может быть пределов", он отчетливо, видит и такие войны, которые ведутся лишь в помощь переговорам и заключаются только в угрозе противнику.

Диалектически подходит Клаузевиц и к путям, ведущим к победе. Наряду с двумя основными видами - войной, стремящейся к сокрушению противника, и войной, разрешающей задачи местного и частного характера - он видит ряд промежуточных форм. Для него ясна невозможность догматизировать какие-либо определенные приемы ведения войны, выбор которых должен определяться исключительно конкретной обстановкой. "Смотря по обстоятельствам, - говорит он, - можно пользоваться с успехом различными подходящими средствами, каковы: уничтожение боевых сил противника, завоевание его провинций, простое их занятие, всякое предприятие, влияющее на политические отношения, и, наконец, пассивное выжидание ударов противника. Выбор каждого из средств зависит от обстановки каждого данного случая".

Клаузевиц ясно устанавливает различие между характером войны в смысле политическом и ее стратегическим характером. "Политически оборонительной войной называется такая война, которую ведут, чтобы отстоять свою независимость; стратегически оборонительной войной называется такой поход, в котором я ограничиваюсь борьбой с неприятелем на том театре военных действий, который себе подготовил для этой цели. Даю ли на этом театре войны сражения наступательного или оборонительного характера, это дела не меняет". Таким образом, политически оборонительная война может быть наступательной в смысле стратегическом и наоборот: "можно и на неприятельской земле, - говорит Клаузевиц, - защищать свою собственную страну".

Диалектика Клаузевица ярко развертывается в его отказе от признания за войной самодовлеющего значения. Несмотря на свой идеализм, он видит, что война "есть особое проявление общественных отношений". Клаузевиц не замыкается поэтому в рамках исследования внешних форм стратегии. Центральным местом в учении Клаузевица является мысль о вырастании войны из политики:"Война есть не что иное, как продолжение государственной политики другими средствами ".

К главе, в которой Клаузевиц особенно подробно рассматривает вопрос о зависимости войны от политики (ч. III, гл. 6), Ленин в своих выписках сделал примечание: "Самая важная глава". [vii]

Крупнейшая заслуга Клаузевица заключается в том, что он решительно отверг представления о войне, как о самостоятельном, независимом от общественного развития явлении.

"...Ни при каких условиях, - пишет Клаузевиц, - мы не должны мыслить войну, как нечто самостоятельное, а как орудие политики. Только при этом представлении возможно избежать противоречия со всей военной историей. Только при этом представлении эта великая книга становится доступной разумному пониманию. Во-вторых, именно это понимание показывает нам, сколь различны должны быть войны по характеру своих мотивов и тем обстоятельствам, из которых они зарождаются".

Вне политики война невозможна. Всегда в человеческом обществе войны вызывались политическими мотивами. "Война в человеческом обществе - война целых народов и притом народов цивилизованных - всегда вытекает из политического состояния и вызывается лишь политическими мотивами", - пишет Клаузевиц.

Клаузевиц рассматривает с этой точки зрения ряд войн в истории и доказывает, что их характер целиком определялся политикой, орудием которой они были.

В свете марксизма-ленинизма этот анализ характера войн прошлой истории очень ограничен и беспомощен, так как исходит из идеалистических представлений Клаузевица об обществе и политике. Но насколько он все же опередил своих современников, показывает тот факт, что до сих пор буржуазные военные теоретики не только не пошли дальше в развитии положений, высказанных великим военным мыслителем, но и остались чужды им.

Крупнейшие теоретики буржуазии до сих пор продолжают рассматривать войну как явление, присущее человеческой природе, вечное и неотвратимое, пока существует мир. На этой позиции стоят все многочисленные буржуазные теории о происхождении войн: биологическая, расовая, психологическая и пр. Назначение их явно заключается в том, чтобы доказать угнетенным классам бессмысленность борьбы против войн, ведущих в интересах капитала.

Клаузевиц, определяя войну как продолжение политики иными средствами, одновременно указывает, что война есть явление особенное, специфическое. "Война есть, - писал он, - определенное дело (и таковым война всегда останется, сколь широкие интересы она не затрагивала бы и даже в том случае, когда на войну призваны все способные носить оружие мужчины данного народа), дело отличное и обособленное". [viii]

Касаясь в другом месте этого вопроса, Клаузевиц говорит, что специфическое в войне относится к природе применяемых ею средств. К сфере специфически военной деятельности относится все, что имеет отношение к вооруженным силам, их организации, сохранению, укреплению, использованию. Однако, отмечая специфику войны, Клаузевиц всюду подчеркивает, что война есть часть целого, а это целое - политика.

Для Клаузевица война - только инструмент политики, особая форма политических отношений. Политика определяет характер войны. Изменения в военном искусстве являются результатом изменения политики. В глазах Клаузевица военное искусство, это - политика, "сменившая перо на меч". Поэтому Клаузевиц решительно борется со всеми попытками подчинить политическую точку зрения военной. Он говорит об этих попытках, как о бессмыслице, "так как политика породила войну. Политика это разум, война же только орудие, а не наоборот".

В свете марксизма-ленинизма трактовка Клаузевицем войны как общественного явления имеет лишь значение величайшего достижения буржуазной военной науки. Коренной порок его теории состоит в идеалистическом понимании политики. Политика для него - выражение интересов всего общества, концентрированный разум государства. Поняв зависимость войны от политики, от общественных условий, Клаузевиц не сумел пойти дальше этого.

Ограниченность буржуазного кругозора лишала Клаузевица возможности понять движущие силы развития самой политики, как исторической формы общественного развития, содержанием которого является классовая борьба. Клаузевиц не видел, что войны порождаются на почве столкновения экономических интересов, на почве классовой борьбы, так как не понимал, что политика - это концентрированная экономика, классовая борьба. И поэтому подлинный характер войн остался для него тайной. Он наивно считал войны "народными", если народные массы в них участвовали, будучи насильственно втянуты в вооруженную борьбу. Он не понимал, что войны Пруссии и других мелких германских государств против Наполеона были народными вовсе не потому, что в них широко участвовали народные массы, в связи с образованием армии на основе всеобщей воинской повинности: они приняли национально-освободительный, "народный" характер лишь тогда, когда началась борьба против диктатуры Наполеона, за национальное освобождение и объединение Германии. Но и в этих условиях союзники Пруссии в 1813-1815 гг. - Англия и Россия Александра I - вели реакционную войну. [ix]

В мировой войне 1914-1918 гг. участвовали огромные массы рабочих и трудящихся. В войну вовлечено было в тех или иных формах почти все население воюющих стран, и вопреки этому война по своему характеру была, конечно, не народной, а наоборот - грабительской, "противонародной", империалистической. Контрреволюционной будет по своему характеру и война империалистических хищников против СССР, тогда как война со стороны пролетарского государства будет войной революционной, справедливой, народной.

Идеалист Клаузевиц не видит классов и классовой борьбы: перед ним всегда - бесформенный "народ".

Изменение общественных отношений и "духа" народа составляет для него необъяснимую тайну. В конечном итоге "дух" становится последней основной пружиной движения и развития общественных отношений и самих войн.

Идеалистическое понимание политики не позволяло этому, поистине глубокому мыслителю разобраться в подлинном характере войн как в истории, так и в современную ему эпоху.

Устанавливая метод своего исследования, Клаузевиц возводит войну на степень абсолютной. Это абстрактное понятие абсолютной войны противопоставляется ее несовершенному отражению - подлинным историческим войнам. Ярко оказавшееся здесь влияние немецкой идеалистической философии приводит к основному противоречию в учении Клаузевица, ибо теория самораскрытия понятия абсолютной войны явно несовместима с его же основным положением о войне, как продолжении политики.

Стратегические взгляды Клаузевица подводят итог тому перевороту в военном деле, который вызвала французская революция. Если по Клаузевицу тактика, это - "учение об использовании вооруженных сил в бою", то стратегия - "учение об использовании боев в целях войны". Центральной решающей задачей полководства Клаузевиц считает организацию генерального сражения, под которым он подразумевает не ординарный бой, каких много на войне, а "... бой главной массы вооруженных сил... с полным напряжением сил за полную победу". Клаузевиц считал, что только великие решительные победы ведут к великим решительным результатам. Отсюда его вывод: "великое решение - только в великом сражении".

Но Клаузевиц знает, что решение стратегических задач вне конкретных условий и задач данной войны - бессмыслица. Это та схоластика, которую ненавидел и против которой боролся К. Клаузевиц - "разве, - спрашивает он, - возможно проектировать план кампании, не учитывая политического состояния и возможностей государства." [x]

Характер политики определяет и характер войны - таково основное положение Клаузевица. "Природа политической цели имеет фактически решающее влияние на ведение войны" - "когда политика становится более грандиозной и мощной, - пишет военный мыслитель, - то таковой же становится и война".

Но правильно устанавливая, что политические уели войны определяют стратегическую линию поведения, Клаузевиц не понимал однако, что характер стратегии обуславливается еще характером вооруженной организации, ее социальной природой, численностью, а также количеством и качеством техники, которой она располагает.

В его трудах отсутствует анализ влияния характера армии на ведение войны. Конечно, он видел разницу между солдатами революции и наемниками, но подлинная сущность армии, ее природа, основы ее дисциплины и боеспособности остались для него тайной.

Клаузевиц уделил в своих работах большое место значению моральных элементов в ведении войны, однако свел все к рассуждениям о военном гении, о доблести армии, о хитрости, твердости, смелости, т.е. к моментам, важным в деле войны, но представляющим собою в отрыве от конкретной действительности пустые абстракции. Наивно звучат, наряду с глубокими мыслями великого теоретика, такие места в его работе: "Воинская доблесть присуща лишь постоянным армиям"; или: "Гений полководца в состоянии заменить дух армии тогда, когда возможно держать ее в сборе".

Клаузевиц не понял также всего значения военной техники, непосредственно обуславливающей способ ведения войны. В тех немногих славах, которые обронил Клаузевиц по поводу военной техники, во весь рост виден его идеализм. Не характер вооружения влияет на ведение войны, а наоборот: "Бой определяет вооружение и устройство войск".

Идеализм Клаузевица, разумеется, несовместим с наукой. Военно-организационная и военно- техническая сторона его теории явно устарели. И все же труды Клаузевица представляют ценнейшее из всего того, что дала буржуазная военная мысль. Именно с этой точки зрения мы рассматриваем Клаузевица и изучаем его теорию.

Марксизм-ленинизм, отдавая должное Клаузевицу, "основные мысли которого сделались в настоящее время безусловным приобретением всякого мыслящего человека" (Ленин), дал принципиально отличное от учения Клаузевица, свободное от идеалистических искажений, единственно научное понимание войны, как "продолжения политики разных классов в данное время". [xi] Ленин в годы империалистической войны тщательно изучал труд Клаузевица. Основное внимание Ленин сосредоточивал на учении Клаузевица об отношении войны к политике и на применении им диалектики к различным сторонам военного дела. Диалектические положения его учения Ленин не раз направлял против софистики социал-шовинистов, против Каутского и Плеханова. В брошюре "Социализм и война" один из разделов озаглавлен прямо цитатой Клаузевица: "Война есть продолжение политики иными (именно: насильственными) средствами". "Это знаменитое изречение, - пишет далее Ленин, - принадлежит одному из самых глубоких писателей по военным вопросам - Клаузевицу. Марксисты справедливо считали всегда это положение теоретической основой взглядов на значение каждой данной войны. Маркс и Энгельс всегда именно с этой точки зрения смотрели на различные войны" (Ленин, Собр. соч., т.XIII, стр. 97).

В статье "Крах II Интернационала" Ленин снова указывает, что "в применении к войнам основное положение диалектики, так бесстыдно извращаемой Плехановым в угоду буржуазии, состоит в том, что "война есть просто продолжение политики другими (именно насильственными) средствами". Такова формулировка Клаузевица, одного из великих писателей по вопросам военной истории, идеи которого были оплодотворены Гегелем. И именно такова была всегда точка зрения Маркса и Энгельса, каждую войну рассматривавших как продолжение политики данных заинтересованных держав и разных классов внутри них в данное время" (Ленин, Собр. соч. т.XIII, стр. 144 - 145). Там же в подстрочном примечании Ленин приводит следующую цитату из Клаузевица: "Все знают, что войны вызываются лишь политическими отношениями между правительствами и между народами; но обыкновенно представляют себе дело таким образом, как будто с начала войны эти отношения прекращаются и наступает совершенно иное положение, подчиненное только своим особым законам. Мы утверждаем наоборот: война есть не что иное, как продолжение политических отношений при вмешательстве иных средств". Это положение В.И. Ленин использует для изобличения софистики Каутского: "Если присмотреться к теоретическим предпосылкам рассуждений Каутского, мы получим именно тот взгляд, который высмеян Клаузевицем около 80 лет тому назад" (Ленин, Собр. соч., т.XIII, стр. 145).

Позже Ленин напоминал о Клаузевице в своей борьбе против "левых" коммунистов. "Мы требуем от всех серьезного отношения к обороне страны, писал Ленин в статье "О "левом" ребячестве [xii] и мелкобуржуазности". Серьезно относиться к обороне страны, это значит основательно готовиться и строго учитывать соотношение сил. Если сил заведомо мало, то важнейшим средством обороны является отступление в глубь страны (тот, кто увидал бы в этом на данный только случай притянутую формулу, может прочитать у старика Клаузевица, одного из великих военных писателей, об итогах уроков истории на этот счет). А у "левых" коммунистов нет и намека на то, чтобы они понимали значение вопроса о соотношении сил" (Ленин, Собр. соч., т.XV, стр. 240 - 241).

Опубликованные в XII Ленинском сборнике выписки и замечания Ленина на книгу Клаузевица "О войне" имеют огромное руководящее методологическое значение: они указывают, как следует читать и изучать труды великого буржуазного теоретика.

Идеалистическое учение Клаузевица нужно нам, разумеется, не для разработки нашей теории войны.

Марксистско-ленинское учение о войне основано на материалистической диалектике. Наша пролетарская теория войны исчерпывающим образом дана в произведениях Маркса, Энгельса, Ленина и Сталина, в решениях нашей партии и ее ЦК. Но проделанный Клаузевицем опыт применения идеалистической диалектики к практической военной деятельности должен быть тщательно и всесторонне учтен нами. Этот критический учет может в известной степени помочь нам пользоваться мощным оружием материалистической диалектики Маркса-Ленина в области анализа конкретной военной действительности.

Настоящее, второе, издание труда Клаузевица "О войне" выходит в свет после необходимой проверки и исправления перевода.

Издательство не сочло нужным сопровождать перевод критическим комментарием и развернутым предисловием, считая совершенно достаточными приводимые книге указания на все сделанные В. И. Лениным выписки и замечания. [xiii]